Posted: 2013/07/15 | Author: amarashiki | Filed under: Basic Neutrinology, Physmatics, The Standard Model: Basics | Tags: bino, dark matter, Dirac mass term, E(6) group, exceptional group GUT, gauginos, GUT, GUT scale, Higgsino, LR models, LSP, Majorana mass term, MSSM, neutralino, neutrino masses, neutrino mixing, proton decay, proton lifetime, R-parity, R-parity violations, seesaw, sfermion, singlets, sneutrino, soft SUSY breaking terms, string inspired models, superparticle, superpartner, superpotential, SUSY models of neutrino masses, vev, WIMPs, wino, Yukawa coupling, Zinos |

Supersymmetry (SUSY) is one of the most discussed ideas in theoretical physics. I am not discussed its details here (yet, in this blog). However, in this thread, some general features are worth to be told about it. SUSY model generally include a symmetry called R-parity, and its breaking provide an interesting example of how we can generate neutrino masses WITHOUT using a right-handed neutrino at all. The price is simple: we have to add new particles and then we enlarge the Higgs sector. Of course, from a pure phenomenological point, the issue is to discover SUSY! On the theoretical aside, we can discuss any idea that experiments do not exclude. Today, after the last LHC run at 8TeV, we have not found SUSY particles, so the lower bounds of supersymmetric particles have been increased. Which path will Nature follow? SUSY, LR models -via GUTs or some preonic substructure, or something we can not even imagine right now? Only experiment will decide in the end…

In fact, in a generic SUSY model, dut to the Higgs and lepton doublet superfields, we have the same  quantum numbers. We also have in the so-called “superpotential” terms, bilinear or trilinear pieces in the superfields that violate the (global) baryon and lepton number explicitly. Thus, they lead to mas terms for the neutrino but also to proton decays with unacceptable high rates (below the actual lower limit of the proton lifetime, about

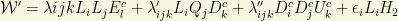

quantum numbers. We also have in the so-called “superpotential” terms, bilinear or trilinear pieces in the superfields that violate the (global) baryon and lepton number explicitly. Thus, they lead to mas terms for the neutrino but also to proton decays with unacceptable high rates (below the actual lower limit of the proton lifetime, about  years!). To protect the proton experimental lifetime, we have to introduce BY HAND a new symmetry avoiding the terms that give that “too high” proton decay rate. In SUSY models, this new symmetry is generally played by the R-symmetry I mentioned above, and it is generally introduced in most of the simplest models including SUSY, like the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM). A general SUSY superpotential can be written in this framework as

years!). To protect the proton experimental lifetime, we have to introduce BY HAND a new symmetry avoiding the terms that give that “too high” proton decay rate. In SUSY models, this new symmetry is generally played by the R-symmetry I mentioned above, and it is generally introduced in most of the simplest models including SUSY, like the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM). A general SUSY superpotential can be written in this framework as

(1)

A less radical solution is to allow for the existence in the superpotential of a bilinear term with structure  . This is the simplest way to realize the idea of generating the neutrino masses without spoiling the current limits of proton decay/lifetime. The bilinear violation of R-parity implied by the

. This is the simplest way to realize the idea of generating the neutrino masses without spoiling the current limits of proton decay/lifetime. The bilinear violation of R-parity implied by the  term leads by a minimization condition to a non-zero vacuum expectation value or vev,

term leads by a minimization condition to a non-zero vacuum expectation value or vev,  . In such a model, the

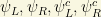

. In such a model, the  neutrino acquire a mass due to the mixing between neutrinos and the neutralinos.The

neutrino acquire a mass due to the mixing between neutrinos and the neutralinos.The  neutrinos remain massless in this toy model, and it is supposed that they get masses from the scalar loop corrections. The model is phenomenologically equivalent to a “3 Higgs doublet” model where one of these doublets (the sneutrino) carry a lepton number which is broken spontaneously. The mass matrix for the neutralino-neutrino secto, in a “5×5” matrix display, is:

neutrinos remain massless in this toy model, and it is supposed that they get masses from the scalar loop corrections. The model is phenomenologically equivalent to a “3 Higgs doublet” model where one of these doublets (the sneutrino) carry a lepton number which is broken spontaneously. The mass matrix for the neutralino-neutrino secto, in a “5×5” matrix display, is:

(2)

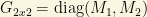

and where the matrix  corresponds to the two “gauginos”. The matrix

corresponds to the two “gauginos”. The matrix  is a 2×3 matrix and it contains the vevs of the two higgses

is a 2×3 matrix and it contains the vevs of the two higgses  plus the sneutrino, i.e.,

plus the sneutrino, i.e.,  respectively. The remaining two rows are the Higgsinos and the tau neutrino. It is necessary to remember that gauginos and Higgsinos are the supersymmetric fermionic partners of the gauge fields and the Higgs fields, respectively.

respectively. The remaining two rows are the Higgsinos and the tau neutrino. It is necessary to remember that gauginos and Higgsinos are the supersymmetric fermionic partners of the gauge fields and the Higgs fields, respectively.

I should explain a little more the supersymmetric terminology. The neutralino is a hypothetical particle predicted by supersymmetry. There are some neutralinos that are fermions and are electrically neutral, the lightest of which is typically stable. They can be seen as mixtures between binos and winos (the sparticles associated to the b quark and the W boson) and they are generally Majorana particles. Because these particles only interact with the weak vector bosons, they are not directly produced at hadron colliders in copious numbers. They primarily appear as particles in cascade decays of heavier particles (decays that happen in multiple steps) usually originating from colored supersymmetric particles such as squarks or gluinos. In R-parity conserving models, the lightest neutralino is stable and all supersymmetric cascade-decays end up decaying into this particle which leaves the detector unseen and its existence can only be inferred by looking for unbalanced momentum (missing transverse energy) in a detector. As a heavy, stable particle, the lightest neutralino is an excellent candidate to comprise the universe’s cold dark matter. In many models the lightest neutralino can be produced thermally in the hot early Universe and leave approximately the right relic abundance to account for the observed dark matter. A lightest neutralino of roughly  GeV is the leading weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) dark matter candidate.

GeV is the leading weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) dark matter candidate.

Neutralino dark matter could be observed experimentally in nature either indirectly or directly. In the former case, gamma ray and neutrino telescopes look for evidence of neutralino annihilation in regions of high dark matter density such as the galactic or solar centre. In the latter case, special purpose experiments such as the (now running) Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (CDMS) seek to detect the rare impacts of WIMPs in terrestrial detectors. These experiments have begun to probe interesting supersymmetric parameter space, excluding some models for neutralino dark matter, and upgraded experiments with greater sensitivity are under development.

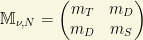

If we return to the matrix (2) above, we observe that when we diagonalize it, a “seesaw”-like mechanism is again at mork. There, the role of  can be easily recognized. The

can be easily recognized. The  mass is provided by

mass is provided by

where  and

and  is the largest gaugino mass. However, an arbitrary SUSY model produces (unless M is “large” enough) still too large tau neutrino masses! To get a realistic and small (1777 GeV is “small”) tau neutrino mass, we have to assume some kind of “universality” between the “soft SUSY breaking” terms at the GUT scale. This solution is not “natural” but it does the work. In this case, the tau neutrino mass is predicted to be tiny due to cancellations between the two terms which makes negligible the vev

is the largest gaugino mass. However, an arbitrary SUSY model produces (unless M is “large” enough) still too large tau neutrino masses! To get a realistic and small (1777 GeV is “small”) tau neutrino mass, we have to assume some kind of “universality” between the “soft SUSY breaking” terms at the GUT scale. This solution is not “natural” but it does the work. In this case, the tau neutrino mass is predicted to be tiny due to cancellations between the two terms which makes negligible the vev  . Thus, (2) can be also written as follows

. Thus, (2) can be also written as follows

(3)

We can study now the elementary properties of neutrinos in some elementary superstring inspired models. In some of these models, the effective theory implies a supersymmetric (exceptional group)  GUT with matter fields belong to the 27 dimensional representation of the exceptional group

GUT with matter fields belong to the 27 dimensional representation of the exceptional group  plus additional singlet fields. The model contains additional neutral leptons in each generation and the neutral

plus additional singlet fields. The model contains additional neutral leptons in each generation and the neutral  singlets, the gauginos and the Higgsinos. As the previous model, but with a larger number of them, every neutral particle can “mix”, making the undestanding of the neutrino masses quite hard if no additional simplifications or assumptions are done into the theory. In fact, several of these mechanisms have been proposed in the literature to understand the neutrino masses. For instance, a huge neutral mixing mass matris is reduced drastically down to a “3×3” neutrino mass matrix result if we mix

singlets, the gauginos and the Higgsinos. As the previous model, but with a larger number of them, every neutral particle can “mix”, making the undestanding of the neutrino masses quite hard if no additional simplifications or assumptions are done into the theory. In fact, several of these mechanisms have been proposed in the literature to understand the neutrino masses. For instance, a huge neutral mixing mass matris is reduced drastically down to a “3×3” neutrino mass matrix result if we mix  and

and  with an additional neutral field

with an additional neutral field  whose nature depends on the particular “model building” and “mechanism” we use. In some basis

whose nature depends on the particular “model building” and “mechanism” we use. In some basis  , the mass matrix can be rewritten

, the mass matrix can be rewritten

(4)

and where the  energy scale is (likely) close to zero. We distinguish two important cases:

energy scale is (likely) close to zero. We distinguish two important cases:

1st. R-parity violation.

2nd. R-parity conservation and a “mixing” with the singlet.

In both cases, the sneutrinos, superpartners of  are assumed to acquire a v.e.v. with energy size

are assumed to acquire a v.e.v. with energy size  . In the first case, the

. In the first case, the  field corresponds to a gaugino with a Majorana mass

field corresponds to a gaugino with a Majorana mass  than can be produced at two-loops! Usually

than can be produced at two-loops! Usually  , and if we assume

, and if we assume  , then additional dangerous mixing wiht the Higgsinos can be “neglected” and we are lead to a neutrino mass about

, then additional dangerous mixing wiht the Higgsinos can be “neglected” and we are lead to a neutrino mass about  , in agreement with current bounds. The important conclusion here is that we have obtained the smallness of the neutrino mass without any fine tuning of the parameters! Of course, this is quite subjective, but there is no doubt that this class of arguments are compelling to some SUSY defenders!

, in agreement with current bounds. The important conclusion here is that we have obtained the smallness of the neutrino mass without any fine tuning of the parameters! Of course, this is quite subjective, but there is no doubt that this class of arguments are compelling to some SUSY defenders!

In the second case, the field  corresponds to one of the

corresponds to one of the  singlets. We have to rely on the symmetries that may arise in superstring theory on specific Calabi-Yau spaces to restric the Yukawa couplings till “reasonable” values. If we have

singlets. We have to rely on the symmetries that may arise in superstring theory on specific Calabi-Yau spaces to restric the Yukawa couplings till “reasonable” values. If we have  in the matrix (4) above, we deduce that a massless neutrino and a massive Dirac neutrino can be generated from this structure. If we include a possible Majorana mass term of the sfermion at a scale

in the matrix (4) above, we deduce that a massless neutrino and a massive Dirac neutrino can be generated from this structure. If we include a possible Majorana mass term of the sfermion at a scale  , we get similar values of the neutrino mass as the previous case.

, we get similar values of the neutrino mass as the previous case.

Final remark: mass matrices, as we have studied here, have been proposed without embedding in a supersymmetric or any other deeper theoretical frameworks. In that case, small tree level neutrino masses can be obtained without the use of large scales. That is, the structure of the neutrino mass matrix is quite “model independent” (as the one in the CKM quark mixing) if we “measure it”. Models reducing to the neutrino or quark mass mixing matrices can be obtained with the use of large energy scales OR adding new (likely “dark”) particle species to the SM (not necessarily at very high energy scales!).

Posted: 2013/07/13 | Author: amarashiki | Filed under: Basic Neutrinology, Physmatics, The Standard Model: Basics | Tags: Dirac mass term, GUT baryon-lepton mass models, GUTs, LR models, magnetic dipole moments, Majorana fermion, Majorana mass term, mass terms, neutrinology, New Physics, pseudo-Dirac fermion, seesaw, seesaw limit, seesaw types, singlet mass term, SO(10), triplet mass term |

Mass terms

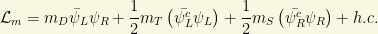

Phenomenologically, lagrangian mass terms can be understood as terms describing “transitions” between right (R) and left (L) handed states in the electroweak sector. For a given minimal, Lorentz invariant set of 4 fields ( ), we have the components of a generic Dirac spinor. Thus, the most general mass part of a (likely extended) electroweak massive lagrangian can be written as follows:

), we have the components of a generic Dirac spinor. Thus, the most general mass part of a (likely extended) electroweak massive lagrangian can be written as follows:

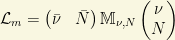

In terms of a “new” Majorana (real) field with  and

and  , we have

, we have

and then, the massive lagrangian becomes

where the neutrino mass matrix is defined to be

We can diagonalize this mass matrix and then we will find the physical particle content! It is given (in general) by two Majorana mass eigenstates: the inclusion of the Majorana mass splits the 4 degenerate states of the Dirac field into two non-degenerate Majorana pairs. If we assume that the states  are respectively “active” (i.e., they belong to some weak doublets) and sterile (weak singlets), then the terms corresponding to the Majorana masses

are respectively “active” (i.e., they belong to some weak doublets) and sterile (weak singlets), then the terms corresponding to the Majorana masses  transform as weak triplets and singlets respectively. While the term corresponding to

transform as weak triplets and singlets respectively. While the term corresponding to  is an standard, weak singlet in most cases, Dirac mass term, its pressence shows to be essential in the next discussion. Indeed, this simple example can be easily generalized to three or more families, in which case the masses beocme matrices themselves. The complete full flavor mixing comes from any two different parts: the diagonalization of the charged lepton Yukawa couplings and that of the neutrino masses! Most of beyond Standard Model theories (specially those coming from GUTs) produce CKM-like leptonic mixing and this mixing is generally “arbitrary” with parameters only to be determined by the experiment. Only when you have an additional gauge symmetry (or some extra discrete symmetry), you can guess some of the mixing parameters from first principles. Therefore, the prediction of the neutrino oscillation/mixing parameters, as for the quark hierarchies and mixing, need further theoretical assumptions NOT included in the Standard Model. For instance, we could require that the

is an standard, weak singlet in most cases, Dirac mass term, its pressence shows to be essential in the next discussion. Indeed, this simple example can be easily generalized to three or more families, in which case the masses beocme matrices themselves. The complete full flavor mixing comes from any two different parts: the diagonalization of the charged lepton Yukawa couplings and that of the neutrino masses! Most of beyond Standard Model theories (specially those coming from GUTs) produce CKM-like leptonic mixing and this mixing is generally “arbitrary” with parameters only to be determined by the experiment. Only when you have an additional gauge symmetry (or some extra discrete symmetry), you can guess some of the mixing parameters from first principles. Therefore, the prediction of the neutrino oscillation/mixing parameters, as for the quark hierarchies and mixing, need further theoretical assumptions NOT included in the Standard Model. For instance, we could require that the  mixing were “maximal” or to impose some “permutation symmetry” and derive the neutrino oscillation parameters from “tribimaximal” or “trimaximal” mixing. However, currently, the symmetry behind the neutrino mass matrix or the quark mixing matrix (the CKM mass matrix) are completely unknown. We can feel and “smell” there are some patterns there (something that suggests a “new” approximate broken symmetry related to flavor) but there is no current accepted working model for the neutrino mass matrix (or its quark analogue, the CKM mass matrix).

mixing were “maximal” or to impose some “permutation symmetry” and derive the neutrino oscillation parameters from “tribimaximal” or “trimaximal” mixing. However, currently, the symmetry behind the neutrino mass matrix or the quark mixing matrix (the CKM mass matrix) are completely unknown. We can feel and “smell” there are some patterns there (something that suggests a “new” approximate broken symmetry related to flavor) but there is no current accepted working model for the neutrino mass matrix (or its quark analogue, the CKM mass matrix).

The seesaw

When we diagonalize the above neutrino mass matrix, we can analyze different “limit” cases. In the case of a purely Dirac mass term, i.e., whenver  , then the

, then the  states are degenerate with mass

states are degenerate with mass  and a four component Dirac field can be “recovered” as

and a four component Dirac field can be “recovered” as  , modulo some constant prefactor. It can be seen that, although violating individual lepton numbers, the Dirac mass term allows a conserve dlepton number

, modulo some constant prefactor. It can be seen that, although violating individual lepton numbers, the Dirac mass term allows a conserve dlepton number  . This case in which the triplet and scalar masses are “tiny” or, equivalently, the case in which their Majorana mass “separation” is very small is sometimes called “pseudo-Dirac” case. In fact, it produces some interesting models both in Cosmology and particle physics. Inded, it could be possible that the 3 neutrino flavors we do know today were, in fact, neutrino (almost degenerated) triplets, i.e., every neutrino flavor could be formed by 3 very close Majorana states that we can not “resolve” using current technology.

. This case in which the triplet and scalar masses are “tiny” or, equivalently, the case in which their Majorana mass “separation” is very small is sometimes called “pseudo-Dirac” case. In fact, it produces some interesting models both in Cosmology and particle physics. Inded, it could be possible that the 3 neutrino flavors we do know today were, in fact, neutrino (almost degenerated) triplets, i.e., every neutrino flavor could be formed by 3 very close Majorana states that we can not “resolve” using current technology.

In the general case, pure Majorana mass transition terms ( ) arise in the lagrangian. Therefore, particle-antiparticle transitions violating the total lepton number by two units do appear (

) arise in the lagrangian. Therefore, particle-antiparticle transitions violating the total lepton number by two units do appear ( ). They can be understood as the creation or annihilation of two neutrinos, and thus, they allow the possibility of the existence of neutrinoless double beta decays! That is, only when the neutrino is a Majorana particle, the channel in which the total lepton number is violated opens.

). They can be understood as the creation or annihilation of two neutrinos, and thus, they allow the possibility of the existence of neutrinoless double beta decays! That is, only when the neutrino is a Majorana particle, the channel in which the total lepton number is violated opens.

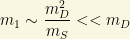

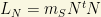

When every mass term is allowed, there is an interesting case commonly referred as “the seesaw” limit. In this limit, taking the triplet mass to be zero and the singlet mass to be “huge” or “superheavy”, we deduce that

with

with  (the “seesaw” limit).

(the “seesaw” limit).

In this seesaw limit, the neutrino mass matrix can be diagonalized and it provides two eigenvalues:

Thus, the seesaw mechanism provide a way in which we obtain two VERY different mass eigenstates, i.e., two single particle states separated by a huge mass hierarchy! There is one (super)heavy neutrino (generally speaking, it corresponds to the right-handed neutrino) and a much lighter neutrino state, one that can be made relatively much lighter than a normal Dirac fermion mass. One fo the neutrino mass is “suppressed” and balanced up (hence the name “seesaw”) by the (super)heavy species. The seesaw mechanism is a “natural” way of generating two different (often VERY separated) mass scales!

The theory of the seesaw mechanism is very rich. I will not discuss its full potential here. There are 3 main types of seesaw mechanisms (generally named as type I, type II and type III) and some other less frequent variants and subvariants…It is an advanced topic for a whole future thread! 😉 However, I will draw you the 3 main Feynman graphs involved in these 3 main types of seesaw mechanisms:

GUTs and neutrino mass models

Any fully satisfactory model that generates neutrino masses must contain a natural mechanism which allows us to explain their samll value, relative to that of their charged partners. Given the latest experimental hints and results, it would also be possible that it will include any comprehensive explanation for light sterile neutrinos and large, nearl maximal, mixing. This last idea is due to some “anomalies” coming from some neutrino experiments (specially those coming from reactors and the celebrated LSND experiment).

Different models can be distinguished according to the new particle content and spectrum, or according to the energy scale hierarchy they produce. With an extended particle content, different options open: if we want to brak the lepton number ant to generate neutrino masses without introducing new (unobserved) fermions in the SM, we must do it by adding to the SM Higgs sector fields carrying lepton numbers. Thus, one can arrange them to break the lepton number explicitly or spontaneously through interactions with these fields. If you want, this is another reason why the Higgs field matters: it allows to introduce fields carrying lepton numbers without adding any extra fermion field! Likely, the most straightforward approach to generate neutrino masses is to introduce for each neutrino an additional weak neutral single (that can be identified with the right-handed neutrino we can not observed due to be “very massive” and/or uncharged under the SM gauge group). This last fact strongly favors seesaw-like models!

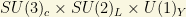

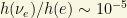

For instance, the above features happen in the framework of LR (Left-Right) symmetric models in Grand Unified Theories (GUTs). There, the origin of the SM parity violation (explicit in the electroweak and weak sectors) is due to the spontaneous symmetry breaking of a baryon-lepton symmetry, and it yields a  quantum number conservation/violation up to a degree that depends on the particular model. Thus, in

quantum number conservation/violation up to a degree that depends on the particular model. Thus, in  GUT, the Majorana neutral particle N enters in a natural way in order to complete the matter multiplet. Therefore, N should be a

GUT, the Majorana neutral particle N enters in a natural way in order to complete the matter multiplet. Therefore, N should be a  singlet, as we wished it to be.

singlet, as we wished it to be.

If we use the energy scale as a guide where the new physics have relevant effects, unification (e.g., think about the previous SO(10) example) and the weak scale approach (radiative models and their effective theories) are usually distinguished and preferred form a pure QFT approach.

Despite the fact that the explanation of the known neutrino anomalies (the solar neutrino problem the first, but also the atmospheric neutrino flux and the reactor anomalies/neutrino beam anomalies) do not need or require the existence of an additional extra light/heavy sterile neutrino, some authors claim that they could exist after all. If every Marojana mass term is “small enough”, then active neutrinos can oscillate or mix into sterile (likely right-handed) fields/states. Light sterile neutrinos can appear in particularly special see-saw mechanisms if additional assumptions are considered (there, some models called “singular seesaw” models do exist as well). with some inevitable amount of “fine tuning”. The alternative to “fine tuning” would be seesaw-like suppression for sterile neutrinos involving new unknown (likely ultraweak or “dark”) interactions, i.e., family symmetries resulting in substantial field additions to the SM (some string theory models also suggest this possibility).

There is also weak scale models, i.e., radiative generated mass models where the neutrino masses are zero at tree level and they constitute a very different type of models: they explain the smallness of the neutrino masses a priori for both active and sterile neutrinos. Loop corrections induce neutrino mass terms in these models. Thus, different mass scales are generated naturally by the different number of loops involved in the generation of each term. The actual implementation requires, however, the ad hoc (a posteriori) introduction of new Higgs particles with non-standard electroweak quantum numbers and lepton number violating couplings. This is the price we pay in an alternative approach.

The origin of the different Dirac and Majorana mass terms  appearing in the neutrino (seesaw like) neutrino mass matrix is usually understood by a dynamical mechanism where at some energy scale it happens “naturally” and/or where some symmetry principle is spontaneously broke and invoked. Firstly, we face with the Dirac mass term. In one special case,

appearing in the neutrino (seesaw like) neutrino mass matrix is usually understood by a dynamical mechanism where at some energy scale it happens “naturally” and/or where some symmetry principle is spontaneously broke and invoked. Firstly, we face with the Dirac mass term. In one special case,  and

and  are SU(2) doublets and singlets respectively. The mass term describes a

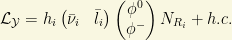

are SU(2) doublets and singlets respectively. The mass term describes a  transition and it is generate from the SU(2) breaking via a Yukawa coupling:

transition and it is generate from the SU(2) breaking via a Yukawa coupling:

Here,  are the components of certain Higgs doublet. The coefficients

are the components of certain Higgs doublet. The coefficients  are the Yukawa couplings. After symmetry breaking,

are the Yukawa couplings. After symmetry breaking,  , where

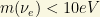

, where  is the vacuum expectation value of the Higgs doublet. A Dirac mass term is qualitatively just like any other fermion mass, but that leads to the question of why it is so small in comparison with the rest of fermion masses: one would require

is the vacuum expectation value of the Higgs doublet. A Dirac mass term is qualitatively just like any other fermion mass, but that leads to the question of why it is so small in comparison with the rest of fermion masses: one would require  in order to have

in order to have  . In other words,

. In other words,  while for the hadronic sector we have

while for the hadronic sector we have  . In principle, it could be that there is no reason beyond the fine tuning of the Yukawa couplings (via Higgs vacuum expectation values to different fields) but, as much as large hierarchies or dimensionless ratios appear, it demands “an explanation”.

. In principle, it could be that there is no reason beyond the fine tuning of the Yukawa couplings (via Higgs vacuum expectation values to different fields) but, as much as large hierarchies or dimensionless ratios appear, it demands “an explanation”.

In the case of the Majorana mass term, the  term will appear if

term will appear if  is a gauge singlet on general grounds. In this case, a renormalizable mass term with structure

is a gauge singlet on general grounds. In this case, a renormalizable mass term with structure

is allowed by the SM gauge group. However, it would bot be consistent in general with unified symmetries or general GUTs. That is, a full SO(10), for instance, and some complicated mechanisms should be used to describe and explain the presence of this term. The  term is usually associated with the breaking of some larger symmetry group, and it is generally expected that its energy scale should be in a range covering from the few hundreds of

term is usually associated with the breaking of some larger symmetry group, and it is generally expected that its energy scale should be in a range covering from the few hundreds of  in LR models to GUTscale energies, or about

in LR models to GUTscale energies, or about  GeV.

GeV.

When the  term is present, then

term is present, then  are active. That is, whenever

are active. That is, whenever  is active, there is a

is active, there is a  term. It belongs to some gauge doublet and it sometimes introduce non-renormalizable interactions. That is the reason why generally speaking models with

term. It belongs to some gauge doublet and it sometimes introduce non-renormalizable interactions. That is the reason why generally speaking models with  are “preferred” over this alternative. In this case, we have

are “preferred” over this alternative. In this case, we have  and

and  must be generated by either:

must be generated by either:

1) An elementary Higgs triplet.

2) An effective operator involving two Higgs doublets arranged to transform as a triplet.

In both cases, we can induce non-renormalizable interactions. In case 1), an elementary triplet  , where

, where  is a Yukawa coupling and

is a Yukawa coupling and  the triplet v.e.v. The simplest realization is the so-called “old Gelmini-Roncadelli model”) and it is EXCLUDED by the LEP data on the Z-invisible width. This last result is due to the fact that the corresponding Majoron particle couples to the Z boson, and it increases significantly its width so we would have seen it at LEP. Some variants of this model involving the explicit lepton number violation or in which the Majoron is mainly a weak singlet (named invisible Majoron models) could still be possible, though, yet. In case 2), for an effective operator originated mass, one should expect

the triplet v.e.v. The simplest realization is the so-called “old Gelmini-Roncadelli model”) and it is EXCLUDED by the LEP data on the Z-invisible width. This last result is due to the fact that the corresponding Majoron particle couples to the Z boson, and it increases significantly its width so we would have seen it at LEP. Some variants of this model involving the explicit lepton number violation or in which the Majoron is mainly a weak singlet (named invisible Majoron models) could still be possible, though, yet. In case 2), for an effective operator originated mass, one should expect  , where

, where  is the scale of new physics wich generates the operator. Let me remark that both cases can trigger non-renormalizability in the extended gauge theory, a property which some people finds “disturbing”.

is the scale of new physics wich generates the operator. Let me remark that both cases can trigger non-renormalizability in the extended gauge theory, a property which some people finds “disturbing”.

Final remarks: If  (typical in LR models), and with typical values of

(typical in LR models), and with typical values of  , one would expect masses about

, one would expect masses about  for the

for the  weak eigenstates, respectively. GUT theories motivates a bigger gap between the intermediate electroweak scale and the GUT scale. The gap can be as large as

weak eigenstates, respectively. GUT theories motivates a bigger gap between the intermediate electroweak scale and the GUT scale. The gap can be as large as  . In the lower end of this range, for

. In the lower end of this range, for  , we have some string-inspired models, GUT with multiple breaking stages and “mixed” models. At the upper end, for

, we have some string-inspired models, GUT with multiple breaking stages and “mixed” models. At the upper end, for  (named GUT seesaw, with large Higgs representations), one typically finds smaller masses for the neutrinos, about

(named GUT seesaw, with large Higgs representations), one typically finds smaller masses for the neutrinos, about  eV respectively for the 3 neutrino flavors (electron, muon and tau). Somehow, this radical approach is more difficult to fit into the present known experimental facts, that they suggest a milielectronvolt neutrino mass as the lighter neutrino mass, up to 1eV (if you consider some experiments as hinting a sterile neutrino as “yet possible”). Thus, neutrinos are hinting to the existence of some intermediate pre-GUT or GUT-like unification energy scale. Where is it? We don’t know! There are many possible models and theories GUT-like. For instance, the next scheme is possible

eV respectively for the 3 neutrino flavors (electron, muon and tau). Somehow, this radical approach is more difficult to fit into the present known experimental facts, that they suggest a milielectronvolt neutrino mass as the lighter neutrino mass, up to 1eV (if you consider some experiments as hinting a sterile neutrino as “yet possible”). Thus, neutrinos are hinting to the existence of some intermediate pre-GUT or GUT-like unification energy scale. Where is it? We don’t know! There are many possible models and theories GUT-like. For instance, the next scheme is possible

Neutrinos and magnetic dipole moments

The magnetic dipole moment is another probe of possible new interactions and physics beyond the Standard Model. Majorana neutrinos have identically zero magnetic and electric dipole moments. Flavor transition magnetic moments are allowed however in general for both Dirac and Majorana neutrinos! Limits obtained from laboratory experiments (LEX) are of the order of a constant times  , where

, where  is the Bohr magneton. There are additional limits/bounds imposed by both stellar physics (or astrophysics) and cosmology in the range

is the Bohr magneton. There are additional limits/bounds imposed by both stellar physics (or astrophysics) and cosmology in the range  . In the SM, the electroweak sector can be extended to allow for Dirac neutrino masses, so that the nuetrino magnetid ipole moment is nonzero and given by

. In the SM, the electroweak sector can be extended to allow for Dirac neutrino masses, so that the nuetrino magnetid ipole moment is nonzero and given by

The proportionality of  to the neutrino mass is due to the absence of an interaction with

to the neutrino mass is due to the absence of an interaction with  in this Dirac extended SM. Then, only its Yukawa coupling appears, and hence, the neutrino mass. In LR symmetric theories (like the mentioned SO(10) theory), the

in this Dirac extended SM. Then, only its Yukawa coupling appears, and hence, the neutrino mass. In LR symmetric theories (like the mentioned SO(10) theory), the  is proportional to the charged lepton mass. Based on general grounds, we find typical values about

is proportional to the charged lepton mass. Based on general grounds, we find typical values about

These values are still too small to have odds of being measurable in current experiments or having practical astrophysical or cosmological consequences we could detect now. However, these magnetic dipole moments are important features of BSM models, so it is important to study them.

Magnetic moment interactions arise in ANY renormalizable gauge theory only as finite radiative corrections. The diagrams which generate a magnetic moment will also contribute to the neutrino mass once the external photon line is removed.In the absence of additional symmetries, a large magnetic moment is incompatible with a small neutrino mass. The way out to this NO-GO theorem suggested by Voloshin consists in defining a  symmetry acting on the flavor space

symmetry acting on the flavor space  , and then the magnetic moment term are singlets under this symmetry. In the limit of exact

, and then the magnetic moment term are singlets under this symmetry. In the limit of exact  symmetry, the neutrino mass is forbidden BUT the magnetic moment

symmetry, the neutrino mass is forbidden BUT the magnetic moment  is allowed. Diverse concrete models have been proposed where such extra symmetry is embedded into an extension of the SM (e.g., in LR models, with SUSY “horizontal” gauge symmetries, by Babu et al.).

is allowed. Diverse concrete models have been proposed where such extra symmetry is embedded into an extension of the SM (e.g., in LR models, with SUSY “horizontal” gauge symmetries, by Babu et al.).

What do you think? Some novel idea? Here you are a decision tree map (LOL):

However, we are far, far away to understand the neutrino hidden higher secrets! Here you are a basic “road map” towards superbeams and neutrino factories, yet an intermediate step before the mythical muon collider (yes, USA likely WANTS that muon collider, :P)…

However, we are far, far away to understand the neutrino hidden higher secrets! Here you are a basic “road map” towards superbeams and neutrino factories, yet an intermediate step before the mythical muon collider (yes, USA likely WANTS that muon collider, :P)…

May the neutrinos be with you!

May the neutrinos be with you!

PS: See you in my next neutrinology blog post!

Posted: 2013/07/13 | Author: amarashiki | Filed under: Basic Neutrinology, Physmatics, The Standard Model: Basics | Tags: AGN, Astrophysics, atmospheric neutrinos, baryogenesis, CMB, CNB, cosmic diffuse neutrino background, cosmic neutrino background, cosmic rays, cosmological models, Cosmology, CP violation, Dirac neutrino, DONUT, double beta decay, E.Fermi, electron, electroweak scale, flavor, gravity, HDM, hot dark matter (HDM), IceCube, inverted hierarchy, KamLAND, leptogenesis, leptons, long baseline experiments, majorana neutrino, massive neutrinos, MINOS, muon, neutrino flavor, neutrino mass, neutrino mass bounds, neutrino mixing, neutrino oscillations, neutrino species, neutrinoless double beta decay, neutrinology, New Physics, NO, NOCILLA, normal hierarchy, NOSEX, quasidegenerated neutrino spectrum, reactor experiment, reactor neutrinos, Reines-Cowan experiment, relic cosmic neutrinos, seesaw, short baseline experiments, SM fermions, SNO, solar neutrino problem, solar neutrinos, Standard Model, Stantadard Cosmological Model, sterile neutrinos, SuperKamiokande, tau particle, W. Pauli, weak interactions |

This new post ignites a new thread.

Subject: the Science of Neutrinos. Something I usually call Neutrinology.

I am sure you will enjoy it, since I will keep it elementary (even if I discuss some more advanced topics at some moments). Personally, I believe that the neutrinos are the coolest particles in the Standard Model, and their applications in Science (Physics and related areas) or even Technology in the future ( I will share my thoughts on this issue in a forthcoming post) will be even greater than those we have at current time.

Let me begin…

The existence of the phantasmagoric neutrinos ( light, electrically neutral and feebly -very weakly- interacting fermions) was first proposed by W. Pauli in 1930 to save the principle of energy conservation in the theory of nuclear beta decay. The idea was promptly adopted by the physics community but the detection of that particle remained elusive: how could we detect a particle that is electrically neutral and that interact very,very weakly with normal matter? In 1933, E. Fermi takes the neutrino hypothesis, gives the neutrino its name (meaning “little neutron”, since it was realized than neutrinos were not Chadwick’s neutrons) and builds his theory of beta decay and weak interactions. With respect to its mass, Pauli initially expected the mass of the neutrino to be small, but necessarily zero. Pauli believed (originally) that the neutrino should not be much more massive than the electron itself. In 1934, F. Perrin showed that its mass had to be less than that of the electron.

By the other hand, it was firstly proposed to detect neutrinos exploding nuclear bombs! However, it was only in 1956 that C. Cowan and F. Reines (in what today is known as the Reines-Cowan experiment) were able to detect and discover the neutrino (or more precisely, the antineutrino). In 1962, Leon M. Lederman, M. Schwartz, J. Steinberger and Danby et al. showed that more than one type of neutrino species  should exist by first detecting interactions of the muon neutrino. They won the Nobel Prize in 1988.

should exist by first detecting interactions of the muon neutrino. They won the Nobel Prize in 1988.

When we discovered the third lepton, the tau particle (or tauon), in 1975 at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, it too was expected to have an associated neutrino particle. The first evidence for this 3rd neutrino “flavor” came from the observation of missing energy and momentum in tau decays. These decays were analogue to the beta decay behaviour leading to the discovery of the neutrino particle.

In 1989, the study of the Z boson lifetime allows us to show with great experimental confidence that only 3 light neutrino species (or flavors) do exist. In 2000, the first detection of tau neutrino ( in addition to

in addition to  ) interactions was announced by the DONUT collaboration at Fermilab, making it the latest particle of the Standard Model to have been discovered until the recent Higgs particle discovery (circa 2012, about one year ago).

) interactions was announced by the DONUT collaboration at Fermilab, making it the latest particle of the Standard Model to have been discovered until the recent Higgs particle discovery (circa 2012, about one year ago).

In 1998, research results at the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector in Japan (and later, independently, from SNO, Canada) determined for the first time that neutrinos do indeed experiment “neutrino oscillations” (I usually call NOCILLA, or NO for short, this phenomenon), i.e., neutrinos flavor “oscillate” and change their flavor when they travel “short/long” distances. SNO and Super-Kamiokande tested and confirmed this hypothesis using “solar neutrinos”. this (quantum) phenomenon implies that:

1st. Neutrinos do have a mass. If they were massless, they could not oscillate. Then, the old debate of massless vs. massive neutrinos was finally ended.

2nd. The solar neutrino problem is solved. Some solar neutrinos scape to the detection in Super-Kamiokande and SNO, since they could not detect all the neutrino species. It also solved the old issue of “solar neutrinos”. The flux of (detected) solar neutrinos was lesser than expected (generally speaking by a factor 2). The neutrino oscillation hypothesis solved it since it was imply the fact that some neutrinos have been “transformed” into a type we can not detect.

3rd. New physics does exist. There is new physics at some energy scale beyond the electroweak scale (the electroweak symmetry breaking and typical energy scale is about 100GeV). The SM is not complete. The SM does (indeed) “predict” that the neutrinos are massless. Or, at least, it can be made simpler if you make neutrinos to be massless neutrinos described by Weyl spinors. It shows that, after the discovery of neutrino oscillations, it is not the case. Neutrinos are massive particles. However, they could be Dirac spinors (as all the known spinors in the Standard Model, SM) or they could also be Majorana particles, neutral fermions described by “Majorana” spinors and that makes them to be their own antiparticles! Dirac particles are different to their antiparticles. Majorana particles ARE the same that their own antiparticles.

In the period 2001-2005, neutrino oscillations (NO)/neutrino mixing phenomena(NEMIX) were observed for the first time at a reactor experiment (this type of experiment are usually referred as short baseline experiment in the neutrino community) called KamLAND. They give a good estimate (by the first time) of the difference in the squares of the neutrino masses. In May 2010, it was reported that physicists from CERN and the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics, in Gran Sasso National Laboratory, had observed for the first time a transformation between neutrino flavors during an accelerator experiment (also called neutrino beam experiment, a class of neutrino experiment belonging to “long range” or “long” baseline experiments with neutrino particles). It was a new solid evidence that at least one neutrino species or flavor does have mass. In 2012, the Daya Bay Reactor experiment in China, and later RENO in South Korea measured the so called  mixing angle, the last neutrino mixing angle remained to be measured from the neutrino mass matrix. It showed to be larger than expected and it was consistent with earlier, but less significant results by the experiments T2K (another neutrino beam experiment), MINOS (other neutrino beam experiment) and Double Chooz (a reactor neutrino experiment).

mixing angle, the last neutrino mixing angle remained to be measured from the neutrino mass matrix. It showed to be larger than expected and it was consistent with earlier, but less significant results by the experiments T2K (another neutrino beam experiment), MINOS (other neutrino beam experiment) and Double Chooz (a reactor neutrino experiment).

With the known value of  there are some probabilities that the

there are some probabilities that the  experiment at USA can find the neutrino mass hierarchy. In fact, beyond to determine the spinorial character (Dirac or Majorana) of the neutrino particles, and to determine their masses (yeah, we have not been able to “weight” the neutrinos, but we are close to it: they are the only particle in the SM with no “precise” value of mass), the remaining problem with neutrinos is to determine what kind of spectrum they have and to measure the so called CP violating processes. There are generally 3 types of neutrino spectra usually discussed in the literature:

experiment at USA can find the neutrino mass hierarchy. In fact, beyond to determine the spinorial character (Dirac or Majorana) of the neutrino particles, and to determine their masses (yeah, we have not been able to “weight” the neutrinos, but we are close to it: they are the only particle in the SM with no “precise” value of mass), the remaining problem with neutrinos is to determine what kind of spectrum they have and to measure the so called CP violating processes. There are generally 3 types of neutrino spectra usually discussed in the literature:

A) Normal Hierarchy (NH):  . This spectrum follows the same pattern in the observed charged leptons, i.e.,

. This spectrum follows the same pattern in the observed charged leptons, i.e.,  . The electron is about 0.511MeV, muon is about 106 MeV and the tau particle is 1777MeV.

. The electron is about 0.511MeV, muon is about 106 MeV and the tau particle is 1777MeV.

B) Inverted Hierarchy (IH):  . This spectrum follows a pattern similar to the electron shells in atoms. Every “new” shell is closer in energy (“mass”) to the previous “level”.

. This spectrum follows a pattern similar to the electron shells in atoms. Every “new” shell is closer in energy (“mass”) to the previous “level”.

C) Quasidegenerated (or degenerated) hierarchy/spectrum (QD):  .

.

While the above experiments show that neutrinos do have mass, the absolute neutrino mass scale is still not known. There are reasons to believe that its mass scale is in the range of some milielectron-volts (meV) up to the electron-volt scale (eV) if some extra neutrino degree of freedom (sterile neutrinos) do appear. In fact, the Neutrino OScillation EXperiments (NOSEX) are sensitive only to the difference in the square of the neutrino masses. There are some strongest upper limits on the masses of neutrinos that come from Cosmology:

1) The Big Bang model states that there is a fixed ratio between the number of neutrino species and the number of photons in the cosmic microwave background (CMB). If the total energy of all the neutrino species exceeded an upper bound about

per neutrino, then, there would be so much mass in the Universe that it would collapse. It does not (apparently) happen.

2) Cosmological data, such as the cosmic microwave background radiation, the galaxy surveys, or the technique of the Lyman-alpha forest indicate that the sum of the neutrino masses should be less than 0.3 eV (if we don’t include sterile neutrinos, new neutrino species uncharged under the SM gauge group, that could increase that upper bound a little bit).

3) Some early measurements coming from lensing data of a galaxy cluster were analyzed in 2009. They suggest that the neutrino mass upper bound is about 1.5eV. This result is compatible with all the above results.

Today, some measurements in controlled experiments have given us some data about the squared mass differences (from both, solar neutrinos, atmospheric neutrinos produced by cosmic rays and accelerator/reactor experiments):

1) From KamLAND (2005), we get

2) From MINOS (2006), we get

There are some increasing efforts to directly determine the absolute neutrino mass scale in different laboratory experiments (LEX), mainly:

1) Nuclear beta decay (KATRIN, MARE,…).

2) Neutrinoless double beta decay (e.g., GERDA; CUORE, Cuoricino, NEMO3,…). If the neutrino is a Majorana particle, a new kind of beta decay becomes possible: the double beta decay without neutrinos (i.e., two electrons emitted and no neutrino after this kind of decay).

Neutrinos have a unique place among all the SM elementary particles. Their role in the cosmic evolution and the fundamental asymmetries in the SM (like CP violating reactions, or the C, T, and P single violations) make them the most fascinating and interesting particle that we know today (well, maybe, today, the Higgs particle is also as mysterious as the neutrino itself). We believe that neutrinos play an important role in Beyond Standard Model (BSM) Physics. Specially, I would like to highlight two aspects:

1) Baryogenesis from leptogenesis. Neutrinos can allow us to understand how could the Universe end in such an state that it contains (essentially) baryons and no antibaryons (i.e., the apparent matter-antimatter asymmetry of the Universe can be “explained”, with some unsolved problems we have not completely understood, if massive neutrinos are present).

2) Asymmetric mass generation mechanisms or the seesaw. Neutrinos allow us to build an asymmetric mass mechanism known as “seesaw” that makes “some neutrino species/states” very light and other states become “superheavy”. This mechanism is unique and, from some non-subjective viewpoint, “simple”.

After nearly a century, the question of the neutrino mass and its origin is still an open question and a hot topic in high energy physics, particle physics, astrophysics, cosmology and theoretical physics in general.

If we want to understand the fermion masses, a detailed determination of the neutrino mass is necessary. The question why the neutrino masses are much smaller than their charged partners could be important! The little hierarchy problem is the problem of why the neutrino mass scale is smaller than the other fermionic masses and the electroweak scale. Moreover, neutrinos are a powerful probe of new physics at scales larger than the electroweak scale. Why? It is simple. (Massive) Neutrinos only interact under weak interactions and gravity! At least from the SM perspective, neutrinos are uncharged under electromagnetism or the color group, so they can only interact via intermediate weak bosons AND gravity (via the undiscovered gravitons!).

If neutrino are massive particles, as they show to be with the neutrino oscillation phenomena, the superposition postulates of quantum theory state that neutrinos, particles with identical quantum numbers, could oscillate in flavor space since they are electrically neutral particles. If the absolute difference of masses among them is small, then these oscillations or neutrino (flavor) mixing could have important phenomenological consequences in Astrophysics or Cosmology. Furthermore, neutrinos are basic ingredients of these two fields (Astrophysics and Cosmology). There may be a hot dark matter component (HDM) in the Universe: simulations of structure formation fit the observations only when some significant quantity of HDM is included. If so, neutrinos would be there, at least by weight, and they would be one of the most important ingredients in the composition of the Universe.

Regardless the issue of mass and neutrino oscillations/mixing, astrophysical interests in the neutrino interactions and their properties arise from the fact that it is produced in high temperature/high density environment, such as collapsing stars and/or supernovae or related physical processes. Neutrino physics dominates the physics of those astrophysical objects. Indeed, the neutrino interactions with matter is so weak, that it passes generally unnoticed and travels freely through any ordinary matter existing in the Universe. Thus, neutrinos can travel millions of light years before they interact (in general) with some piece of matter! Neutrinos are a very efficient carrier of energy drain from optically thick objects and they can serve as very good probes for studying the interior of such objects. Neutrino astronomy is just being born in recent years. IceCube and future neutrino “telescopes” will be able to see the Universe in a range of wavelengths and frequencies we have not ever seen till now. Electromagnetic radiation becomes “opaque” at some very high energies that neutrinos are likely been able to explore! Isn’t it wonderful? Neutrinos are high energy “telescopes”!

By the other hand, the solar neutrino flux is, together with heliosysmology and the field of geoneutrinos (neutrinos coming from the inner shells of Earth), some of the known probes of solar core and the Earth core. A similar statement applies to objects like type-II supernovae. Indeed, the most interesting questions around supernovae and the explosion dynamics itself with the shock revival (and the synthesis of the heaviest elements by the so-called r-processes) could be positively affected by changes in the observed neutrino fluxes (via some processes called resonant conversion, and active-sterile conversions).

Finally, ultra high energy neutrinos are likely to be useful probes of diverse distant astrophysical objects. Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) should be copious emitters of neutrinos, providing detectable point sources and and observable “diffuse” background which is larger in fact that the atmospheric neutrino background in the very high energy range. Relic cosmic neutrinos, their thermal background, known as the cosmic neutrino background, and their detection about 1.9K are one of the most important lacking missing pieces in the Standard Cosmological Model (LCDM).

Do you understand why neutrinos are my favorite particles? I will devote this basic thread to them. I will make some advanced topics in the future. I promise.

May the Neutrinos be with you!

quantum numbers. We also have in the so-called “superpotential” terms, bilinear or trilinear pieces in the superfields that violate the (global) baryon and lepton number explicitly. Thus, they lead to mas terms for the neutrino but also to proton decays with unacceptable high rates (below the actual lower limit of the proton lifetime, about

years!). To protect the proton experimental lifetime, we have to introduce BY HAND a new symmetry avoiding the terms that give that “too high” proton decay rate. In SUSY models, this new symmetry is generally played by the R-symmetry I mentioned above, and it is generally introduced in most of the simplest models including SUSY, like the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM). A general SUSY superpotential can be written in this framework as

. This is the simplest way to realize the idea of generating the neutrino masses without spoiling the current limits of proton decay/lifetime. The bilinear violation of R-parity implied by the

term leads by a minimization condition to a non-zero vacuum expectation value or vev,

. In such a model, the

neutrino acquire a mass due to the mixing between neutrinos and the neutralinos.The

neutrinos remain massless in this toy model, and it is supposed that they get masses from the scalar loop corrections. The model is phenomenologically equivalent to a “3 Higgs doublet” model where one of these doublets (the sneutrino) carry a lepton number which is broken spontaneously. The mass matrix for the neutralino-neutrino secto, in a “5×5” matrix display, is:

corresponds to the two “gauginos”. The matrix

is a 2×3 matrix and it contains the vevs of the two higgses

plus the sneutrino, i.e.,

respectively. The remaining two rows are the Higgsinos and the tau neutrino. It is necessary to remember that gauginos and Higgsinos are the supersymmetric fermionic partners of the gauge fields and the Higgs fields, respectively.

GeV is the leading weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) dark matter candidate.

can be easily recognized. The

mass is provided by

and

is the largest gaugino mass. However, an arbitrary SUSY model produces (unless M is “large” enough) still too large tau neutrino masses! To get a realistic and small (1777 GeV is “small”) tau neutrino mass, we have to assume some kind of “universality” between the “soft SUSY breaking” terms at the GUT scale. This solution is not “natural” but it does the work. In this case, the tau neutrino mass is predicted to be tiny due to cancellations between the two terms which makes negligible the vev

. Thus, (2) can be also written as follows

GUT with matter fields belong to the 27 dimensional representation of the exceptional group

plus additional singlet fields. The model contains additional neutral leptons in each generation and the neutral

singlets, the gauginos and the Higgsinos. As the previous model, but with a larger number of them, every neutral particle can “mix”, making the undestanding of the neutrino masses quite hard if no additional simplifications or assumptions are done into the theory. In fact, several of these mechanisms have been proposed in the literature to understand the neutrino masses. For instance, a huge neutral mixing mass matris is reduced drastically down to a “3×3” neutrino mass matrix result if we mix

and

with an additional neutral field

whose nature depends on the particular “model building” and “mechanism” we use. In some basis

, the mass matrix can be rewritten

energy scale is (likely) close to zero. We distinguish two important cases:

are assumed to acquire a v.e.v. with energy size

. In the first case, the

field corresponds to a gaugino with a Majorana mass

than can be produced at two-loops! Usually

, and if we assume

, then additional dangerous mixing wiht the Higgsinos can be “neglected” and we are lead to a neutrino mass about

, in agreement with current bounds. The important conclusion here is that we have obtained the smallness of the neutrino mass without any fine tuning of the parameters! Of course, this is quite subjective, but there is no doubt that this class of arguments are compelling to some SUSY defenders!

corresponds to one of the

singlets. We have to rely on the symmetries that may arise in superstring theory on specific Calabi-Yau spaces to restric the Yukawa couplings till “reasonable” values. If we have

in the matrix (4) above, we deduce that a massless neutrino and a massive Dirac neutrino can be generated from this structure. If we include a possible Majorana mass term of the sfermion at a scale

, we get similar values of the neutrino mass as the previous case.

You must be logged in to post a comment.